Home automation best practices

After having spent a lot of time and effort installing smart devices throughout my entire house and automating them, I’ve learned a lot of do’s and don’ts. It’s been a long process of trial and error to come up with the right automations that work for all scenarios. Along the way, certain patterns and practices emerged that made it easier for me to setup automations correctly the first time and sparked joy for everybody in my household.

I’ve also come to believe that most of these practices are not specific to my household but are universal in nature and can be used by other home automation enthusiasts. Since I couldn’t find anything similar online, I thought I’d share these practices here in case you find them useful.

Here we go:

Works for everybody

Every member of the household and guests must have a neutral to positive experience with the automations. Few things are more annoying than having lights turn off in the bathroom while you are in there or accidently triggering the alarm system’s siren while the baby is sleeping.

Especially guests that are less familiar with any automations can be annoyed if not done correctly.

An example would be our spare room which turns the lights on when you enter and turns it off after a minute of no motion. It works flawlessly for everyday use, but we also use it as an occasional guest room. My mom came to visit for 2 weeks and experienced having the lights go on and off at inconvenient times – when taking a nap for instance. The automation wasn’t designed for that use pattern. The fix was to install a door sensor and disable all automations in the room when the door was closed.

Another example is our guest bathroom lights which automatically turn on when people enter. In the beginning, the placement of the motion sensor and the logic of the automation resulted in a short delay from entering until the lights came on. The consequence was that people’s muscle memory had them reaching for the light switch. But once clicked, the automatic lights had just been activated so the result was the lights turned off instead of on. The fix was to place the motion sensor in a better location and to optimize the automation logic for speedy execution. Now the lights come on without delay and people’s muscle memory to turn on the switch isn’t triggered.

This rule can be hard to adhere to when you first create the individual automations. Sometimes only real-life usage will reveal cracks in the logic that need fixing.

Adapts to natural behavior

Home automation systems should improve people’s lives. As such, the automations must work in ways that follow the natural behavior of the people it serves. It’s an easy pitfall to build automations that works perfectly when people use it in the “correct” way, but if that is not how people behave in real life, then the automation needs adjustment.

An example are my linen closet lights. The automation would turn on the lights when the door opened and turn it back off when it closed. Sounds simple enough and it worked great. Except for the fact that to close the door, we would often just push it ajar leaving it not fully closed. In those situations, the light wouldn’t turn off and the automation seemed broken to us. The fix was to move the door sensor from the corner of the door to a location where almost closed was understood by the automation as closed.

No further explanation needed

When the smart home works for everybody and adapts to the natural behavior of people in it, it shouldn’t be necessary to explain how it all works. However, some automations work beyond people’s natural behavior and are not discoverable unless taught. Once learned, using the automations should become a natural behavior for people.

An example could be a smart light switch that supports double tapping as a trigger to control multiple lights in the room. You cannot tell that the light switch has this feature, so unless you are told about it, you don’t know. One way people can take advantage of these hidden features is to make them into a pattern throughout the house. The pattern could be that double tapping any light switch will turn on/off all lights in the same room. You could even mark the switches with this capability for easy visual identification. Once taught, people can apply that same logic to any room and no further explanation is needed.

Resiliency built in

When your internet is down or the smart home hub fails, the smart home must still be functional. All lights must be operational from switches, the door locks still able to let you in etc. It’s ok that the automations don’t all work. In other words, the smart home must fail gracefully.

An example of when it doesn’t fail gracefully is when the internet in our house went down for a few days after a major snow storm. The smart home hub was still working, but it could only execute the automations that didn’t require an internet connection and I couldn’t use the app to control it either for the same reason. So, I couldn’t stop some automations from happening such as lights going on in bedrooms at the middle of the night, because the house wasn’t able to put itself into night mode without internet. I had to unplug the hub.

After we regained our internet connection and plugged the hub back in, I made a bunch of changes to ensure that all essential automations would run locally (meaning no internet required), and that the non-essentials would fail gracefully. I also made sure to be able to control various states and variables through physical switches and buttons so I can disable some automations in case internet connection is lost again.

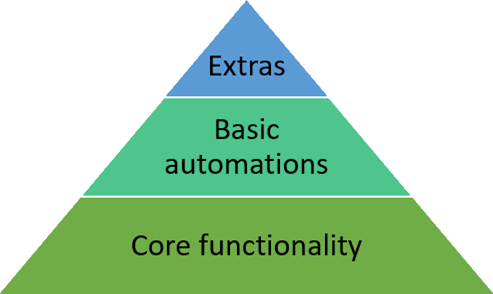

A way of thinking about this is to approach home automation as steps of a pyramid. Each step in the pyramid requires the existence of the one below it and should be completely independent of any steps above it.

Core functionality

Start at the bottom where the core functionality must always be operational. Only a power outage can disable the core functionality. In practice, this means that when the smart home hub and/or internet is down, the smart home gracefully degrades back into a fully functioning dumb home.

Examples are all lights, fans, door locks, and thermostats which should be operational from their physical controls such as a wall switch.

Basic automations

If something happened that only allows some automations to work, make sure they are the basic automations. It would most likely be lighting, door locks and such that is to be considered basic, but it is up to each smart home to determine which automations are of a more essential nature. Make sure this step can be executed fully locally and doesn’t have any dependencies on the Extras step above it.

Examples are door- and motion sensor-based lighting automations, as well as bathroom fan and thermostat operations.

Extras

The Extras are non-essential automations and ones that require an internet connection. We want to keep this step as small as possible since these automations are the ones that are likely to break down first.

Examples would be automations/controls initiated through voice assistants such as Amazon Echo or Google Home. It is also anything that require an internet connection such as certain types of Wi-Fi switches, plugs and light bulbs.

I really enjoy automating our home and I look forward to sharing more learnings, tips, tricks and other stories in the future.